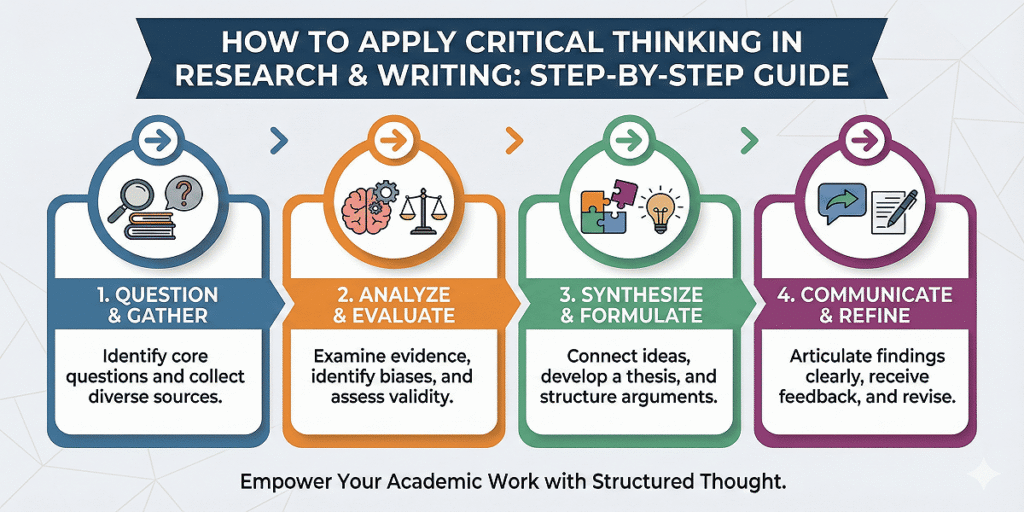

Applying critical thinking in research and writing is important. It transforms academic work from passive information gathering into active intellectual engagement.

Critical thinking means:

- Questioning assumptions

- Evaluating evidence systematically

- Recognising biases

- Analysing arguments logically

- Constructing well-reasoned conclusions supported by credible sources

It’s the difference between summarising what others say and developing your own informed perspective through rigorous analysis.

This step-by-step guide shows exactly how to integrate critical thinking throughout your research and writing process, from initial question formulation through final revision.

Critical Thinking vs. Basic Thinking

| Basic Thinking | Critical Thinking |

| Accepts information at face value | Questions sources and assumptions |

| Summarises what others say | Evaluates arguments and evidence |

| Reports facts without analysis | Analyses relationships and patterns |

| Relies on single perspectives | Considers multiple viewpoints |

| Follows instructions passively | Engages actively with material |

| Avoids challenging ideas | Examines contradictions thoughtfully |

Step 1: Identify and Refine the Research Question

Start by clearly defining your problem or topic. Vague questions produce vague research.

“Write about climate change” > gives no direction.

“How do carbon pricing mechanisms compare to regulatory approaches in reducing industrial emissions?” > provides focus.

Ask “why” and “how” questions to move beyond simple facts.

- What causes this?

- How do factors interact?

- Why does this pattern exist?

These questions force analytical thinking rather than descriptive reporting.

Determine why your topic matters and who it affects. Understanding stakes helps you identify what perspectives and evidence matter most.

Let’s say:

- Weak: “What is artificial intelligence?”

- Strong: “How does AI implementation in NHS diagnostics balance efficiency gains against patient privacy concerns?”

Step 2: Actively Locate and Evaluate Sources

Look for credible sources. Peer-reviewed journals. Academic books. Reputable research institutions. Not all information deserves equal weight. Critical thinkers distinguish reliable evidence from questionable claims.

Analyse sources for potential bias, author credentials, and methodology.

- Who wrote this?

- What’s their expertise?

- Who funded the research?

For example, pharmaceutical company-funded drug studies require more scrutiny than independent university research.

Ask yourself:

- What assumptions does the author hold?

- What evidence supports their argument?

- What contradicting evidence haven’t they addressed?

- Are there alternative explanations they’ve overlooked?

Critical thinking application:

Don’t just collect sources. Interrogate them. When authors claim “studies show,” ask which studies, how many, what quality, what limitations.

Step 3: Analyse and Synthesise Information

Compare findings across different sources to identify patterns, correlations, or contradictions.

Critical thinking thrives on comparison. When three studies reach similar conclusions using different methodologies, that strengthens confidence. When reputable sources contradict each other, that signals complexity requiring careful navigation rather than simple answers.

Determine how sources support or refute your working thesis.

Not every source will neatly support your position. That’s valuable. Sources challenging your initial thinking force you to refine arguments, acknowledge limitations, or sometimes change your position entirely based on evidence. This intellectual flexibility demonstrates critical thinking, not weakness.

Connect ideas between sources to build coherent arguments.

Synthesis means creating a new understanding by combining insights from multiple sources.

- Author A identifies a problem.

- Author B proposes a solution.

- Author C provides evidence about implementation challenges.

Your synthesis integrates these perspectives into a nuanced argument that none of the perspectives presented individually.

Critical thinking application:

Create comparison charts tracking what each source says about key questions. This visual organisation helps you spot where consensus exists, where disagreement emerges, and where gaps in knowledge remain. All critical for developing informed positions.

Step 4: Formulate Your Own Argument (Synthesis)

Develop a clear thesis statement that reflects your analysis.

Your thesis shouldn’t just restate what sources say. It should present your reasoned conclusion based on evaluating available evidence.

Weak: “Experts disagree about climate policy.”

Strong: “Whilst carbon pricing offers theoretical efficiency, implementation evidence suggests regulatory approaches achieve more consistent emissions reductions in contexts with weak governance structures.”

Propose alternative interpretations or better approaches to problems.

Critical thinking involves not just understanding existing debates but potentially offering fresh perspectives. Perhaps the literature frames an issue in binary terms when reality is more complex. Perhaps commonly accepted solutions overlook practical barriers you’ve identified through analysis.

Address potential counterarguments to strengthen your position.

Anticipate objections.

- Why might someone disagree with your thesis?

- What’s the strongest case against your position?

Addressing these directly, rather than ignoring them, demonstrates intellectual rigor and strengthens your argument by showing you’ve considered alternatives.

Critical thinking application:

Test your thesis by trying to argue against it. If you can’t construct a reasonable counterargument, you may not fully understand the debate’s complexity. The ability to steelman opposing views (present them in their strongest form) before explaining why your position remains more convincing demonstrates sophisticated critical thinking.

Step 5: Structure and Write with Evidence

Organise your paper logically with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

Structure supports thinking. Each paragraph should develop one clear idea connecting to your thesis. Readers should follow your reasoning step-by-step, understanding how each piece builds toward your conclusion.

Use topic sentences connecting paragraphs back to your thesis.

Every paragraph should obviously relate to your central argument. If a paragraph’s connection to your thesis isn’t clear, it probably doesn’t belong or needs rewriting to clarify relevance.

Support every claim with concrete evidence and data.

Critical thinking demands evidence.

Don’t write “many people believe” when you can write “recent surveys indicate 67% of respondents…”

Don’t claim “research shows” without citing specific studies. Vague appeals to unnamed authorities signal weak thinking.

Critical thinking application:

For each claim you make, ask yourself:

- How do I know this?

- What evidence supports it?

- Could a skeptical reader reasonably question this without additional support?

This self-interrogation catches unsupported assertions before submission.

Step 6: Review, Reflect, and Revise

Evaluate your own work for clarity, coherence, and logical flow.

Critical thinking applies to your own writing, not just others’ work. Make sure:

- Does your argument make sense?

- Do paragraphs connect logically?

- Have you explained your reasoning clearly or assumed readers will follow intuitive leaps?

Check if arguments are well-supported and free of unsupported assumptions.

Common assumption traps, such as:

- Confusing correlation with causation

- Assuming small samples represent larger populations

- Treating complex issues as simple binaries

- Claiming one factor explains outcomes with multiple contributing causes

Reflect on the process:

- Did I consider all relevant perspectives?

- Are there gaps in my reasoning?

- What would strengthen this argument?

- What limitations should I acknowledge?

Critical thinking application:

Read your work as if you’re a skeptical examiner looking for weaknesses.

- Where would they challenge your reasoning?

- What questions would they ask?

Anticipating criticism helps you address it proactively, strengthening final submissions significantly.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How is critical thinking different from just criticising everything?

Critical thinking means fair evaluation based on evidence and logic, not knee-jerk negativity. You critically assess both strengths and weaknesses. Sometimes, critical analysis concludes that an argument is strong and well-supported. That’s valid critical thinking, too.

Q2: Can I develop critical thinking skills quickly, or does it take time?

Critical thinking improves with deliberate practice over time. Start by consciously applying these steps to smaller assignments. Question one assumption per paragraph. Compare two sources explicitly. These small practices compound into stronger overall skills.

Q3: What if the critical analysis of sources contradicts what my lecturer taught?

Respectfully present evidence supporting your analysis. Academia values well-reasoned arguments backed by credible sources. However, ensure you’ve understood the lecturer’s position fully before claiming contradiction. Misunderstanding differs from genuine disagreement.

Q4: How many sources do I need to demonstrate critical thinking?

Quality matters more than quantity. Five thoroughly analysed, compared sources demonstrate more critical thinking than fifteen briefly mentioned ones. Focus on deep engagement with credible sources rather than accumulating citations.

Q5: Is critical thinking the same across all subjects?

Core principles apply universally, questioning assumptions, evaluating evidence, and considering alternatives. But disciplines emphasise different aspects. The sciences prioritise methodology evaluation; the humanities focus more on interpretation and perspective analysis. Adapt critical thinking frameworks to your field.

Q6: What if I can’t find sources that disagree with each other?

Widespread consensus can exist on some topics. That’s legitimate. Critical thinking then involves understanding why consensus exists, what evidence created it, and whether any limitations or contexts where it might not apply remain worth exploring.

Conclusion

Applying critical thinking in research and writing isn’t an optional extra. It’s fundamental to academic success.

These six steps transform how you approach every assignment:

- Questioning strategically

- Evaluating evidence rigorously

- Synthesising insights thoughtfully

- Arguing persuasively

- Structuring logically

- Revising critically

Each step builds intellectual skills extending far beyond university into professional life and informed citizenship.

But developing critical thinking takes practice, feedback, and sometimes expert guidance when you’re uncertain whether your analysis demonstrates the depth UK universities demand.

Assignment Help service in London, UK supports you in developing critical thinking skills across all academic writing. Our UK-qualified experts model how to question assumptions, evaluate sources, construct evidence-based arguments, and structure critical analysis effectively for your specific discipline.

Whether you need:

- Essay writing demonstrating critical evaluation

- Research papers requiring rigorous analysis

- Dissertations demanding sophisticated synthesis

- Coursework integrating critical thinking throughout

We provide examples and explanations showing how critical thinking translates into academic writing.

We don’t just complete assignments. We help you understand how critical thinkers actually approach research and writing.

At FQ Assignment help in UK, your intellectual development matters. We support that journey.