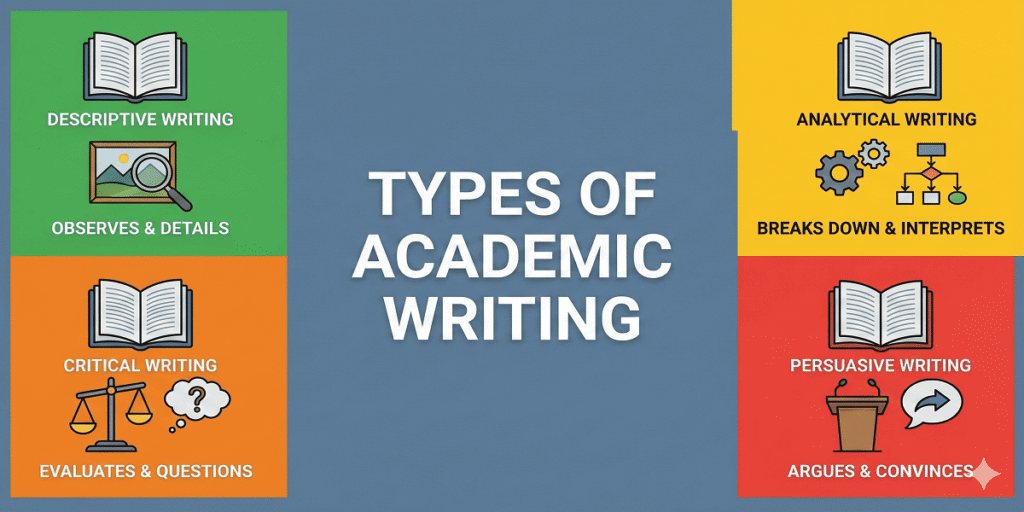

Academic writing operates across three major progressive levels of academic writing, oftentimes called types of academic writing:

- Descriptive writing

- Analytical writing

- Critical writing

- Persuasive Writing

Each represents increasingly sophisticated engagement with ideas, evidence, and arguments.

Progressive levels of academic writing refer to hierarchical stages of intellectual engagement. From reporting information, to examining relationships, to evaluating validity and constructing informed judgements.

Descriptive writing means presenting facts or information without interpretation. Simply stating what happened or exists.

Analytical writing refers to examining components, identifying patterns, and explaining relationships, breaking down information to understand how parts connect.

Critical writing involves evaluating arguments, assessing evidence quality, and developing informed judgements about validity. The highest level of academic thinking.

Persuasive writing refers to presenting arguments designed to convince readers to accept a specific viewpoint, take particular action, or change their perspective through rhetorical strategies and compelling evidence.

Understanding these distinctions transforms academic work from basic reporting to sophisticated scholarly engagement.

Descriptive Writing

What is Descriptive Writing?

Descriptive writing is presenting factual information or summarising content without adding analysis, interpretation, evaluation, or judgement about significance or validity.

How Descriptive Writing Differs From Others

Descriptive vs Analytical:

Descriptive: “Smith (2023) found that 68% of participants reported high anxiety during exam periods.”

Analytical: “Smith’s (2023) findings reveal a correlation between exam periods and increased anxiety, suggesting assessment timing significantly influences student mental health.”

Descriptive reports facts. Analytical writing examines relationships and explains meaning.

Descriptive vs Critical:

Descriptive: “Jones (2022) argues social media causes teenage depression based on surveying 500 adolescents.”

Critical: “Whilst Jones (2022) claims causation, the limited sample (500 students, three schools) and self-reported data raise questions about the generalisability of these causal conclusions.”

Descriptive states research claims. Critical evaluation evaluates claim strength and identifies limitations.

How to Do Descriptive Writing

Don’ts of Descriptive Writing

Don’t mistake description for analysis. Simply reporting what sources say doesn’t demonstrate understanding. UK universities expect engagement with material, not just summarisation. Use descriptive passages to support analysis, not replace it entirely.

Don’t rely predominantly on description at higher academic levels. Whilst appropriate for background sections, descriptive writing as your primary approach in Level 5+ or postgraduate work signals insufficient critical engagement with material.

Do’s of Descriptive Writing

Do use description strategically for establishing context. Opening sections often require descriptive passages explaining background information, defining terms, or outlining current understanding before analysing or critiquing. This foundation supports subsequent critical engagement effectively.

Do present information clearly and accurately. Ensure statistics are reported correctly, represent authors’ arguments fairly, and maintain logical sequence. Even a basic description demands precision without introducing premature interpretation.

Do recognise when description suffices for your purpose. Methodology sections, case study backgrounds, or historical timelines often appropriately use primarily descriptive writing. Understanding when description serves your aims prevents unnecessary complexity.

Analytical Writing

What is Analytical Writing?

Analytical writing is examining how components relate, identifying patterns, explaining significance, and breaking down information to explore connections.

How Analytical Writing Differs From Others

Analytical vs Descriptive:

Descriptive: “The study examined three teaching methods: lectures, seminars, and independent study. Performance was measured through exams.”

Analytical: “Comparing three teaching methods reveals that whilst lectures efficiently convey foundational knowledge, seminars and independent study correlate with higher-order thinking, suggesting learning outcomes depend on pedagogical approach alignment with cognitive objectives.”

Descriptive states what happened. An analytical writer explains relationships and interprets significance.

Analytical vs Critical:

Analytical: “Data indicates positive correlation between exercise and academic performance, with students exercising 3+ times weekly scoring 12% higher than sedentary peers.”

Critical: “Whilst correlation appears strong, failure to control for confounding variables, socioeconomic status, prior achievement, and time management, means this relationship may be associative rather than causal.”

An analytical writing expert identifies patterns. Critical evaluation of the conclusion’s strength and considers limitations.

How to Do Analytical Writing

Don’ts of Analytical Writing

Don’t present analysis as a simple observation. Stating “the data shows” without explaining what that means stops short of genuine analysis. Identify patterns, then interpret their significance or implications for understanding the topic.

Don’t confuse categorisation with analysis. Grouping information into themes represents organisation, not analysis. Analysis requires explaining why categories matter, how they relate, or what patterns they reveal about your subject.

Do’s of Analytical Writing

Do explain the “so what” of the presented information. After presenting evidence, clarify significance: What does this pattern reveal? Why does this relationship matter? How does this support your developing argument?

Do use comparative analysis to strengthen arguments. Examining similarities and differences between theories, cases, or studies reveals patterns that simple description cannot. Comparison naturally moves writing from descriptive to analytical levels.

Do employ analytical vocabulary signalling relationships. Words like “consequently,” “this suggests,” “in contrast,” and “this pattern indicates” explicitly mark analytical thinking, helping readers follow your interpretation rather than just receiving facts.

Critical Writing

What is Critical Writing?

Critical writing is evaluating arguments’ validity, assessing evidence quality, identifying assumptions and limitations, and constructing informed judgements about claims’ credibility.

How Critical Writing Differs From Others

Critical vs Descriptive:

Descriptive: “Brown (2021) states renewable energy provides sustainable alternatives. The study examined wind and solar across five European countries.”

Critical: “Brown’s (2021) optimistic assessment overlooks implementation challenges. Whilst demonstrating technical feasibility, failure to address economic barriers, political resistance, or storage limitations undermines widespread sustainability claims.”

Descriptive reports research. Critical evaluates claims and identifies overlooked factors.

Critical vs Analytical:

Analytical: “Research reveals online platforms increase rural access whilst reducing costs, suggesting technological solutions can address educational barriers.”

Critical: “Although online platforms reduce geographical barriers, this assumes equal technological access. Contradicted by digital divide evidence. Cost analysis also excludes hidden expenses like internet or devices, potentially overstating accessibility improvements.”

Analytical identifies patterns. Critical questions, assumptions, and evaluate whether conclusions are fully supported.

How to Do Critical Writing

Don’ts of Critical Writing

Don’t just summarise. Critical writing demands evaluation, not description. Assess whether arguments convince, whether evidence supports claims adequately, and whether conclusions follow logically from presented evidence.

Don’t use emotive language. Critical evaluation requires objective assessment, not emotional reaction. Replace “terrible study” with “methodologically flawed study.” Avoid loaded language, substituting assertion for reasoned evaluation.

Don’t ignore limitations. Acknowledge when evidence is inconclusive, data contradict claims, or methodological flaws undermine conclusions. Pretending weaknesses don’t exist damages credibility more than weaknesses themselves.

Don’t overgeneralise. Avoid sweeping statements. Instead of “this theory is wrong,” write “this theory inadequately accounts for X.” Nuanced evaluation demonstrates sophisticated thinking; absolute judgements suggest oversimplification.

Don’t use informal language. Critical academic writing requires a formal register. Avoid slang and colloquialisms. Replace “kind of shows” with “suggests” or “indicates” for an appropriate academic tone.

Don’t ask rhetorical questions. Convert questions into direct statements. Replace “Can we trust this data?” with “The data reliability merits scrutiny given the sampling methodology employed.”

Do’s of Critical Writing

Do analyse and evaluate. Move beyond description to assess evidence strength and argument quality. Ask: Is the evidence sufficient? Does the methodology suit the question? Do conclusions logically follow from findings?

Do take a position. Develop clear, focused arguments supported with evaluated evidence. Critical writing means making informed judgements whilst acknowledging complexity and uncertainty where appropriate, not fence-sitting.

Do be objective and precise. Use formal, precise language and the clear present tense for discussing research. Replace vague terms with specifics. Instead of “many studies,” specify “three meta-analyses” with citations.

Do integrate sources critically. Analyse quoted material rather than using it as an argument substitute. After presenting sources, evaluate: Does evidence support claims? What are this study’s limitations?

Do consider counterarguments. Acknowledge alternative perspectives to strengthen your position. Addressing opposing views demonstrates comprehensive engagement and allows for explaining why your position remains most convincing.

Do structure logically. Use clear topic sentences and signposting to guide readers. Phrases like “however,” “despite this,” and “conversely” signal shifts, helping readers follow your critical analysis.

Persuasive Writing

What is Persuasive Writing?

Persuasive writing is constructing arguments specifically designed to convince readers to accept your position, change their behaviour, or adopt your perspective through strategic evidence and rhetorical techniques.

How Persuasive Writing Differs From Others

Persuasive vs Descriptive:

Descriptive: “University tuition fees in England currently stand at £9,250 annually. Students graduate with average debts of £45,000.”

Persuasive: “University tuition fees of £9,250 annually burden students with crippling £45,000 debts, pricing out working-class students and undermining social mobility. The government must reduce fees immediately to ensure education remains accessible to all, regardless of background.”

Descriptive reports facts neutrally. Persuasive uses facts to advocate for a specific action or viewpoint.

Persuasive vs Analytical:

Analytical: “Rising tuition fees correlate with decreased enrollment from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, suggesting financial barriers significantly influence higher education access patterns across demographic groups.”

Persuasive: “Rising tuition fees don’t just correlate with decreased working-class enrollment. They actively exclude talented students who cannot afford an education. We must eliminate these barriers by returning to grant-funded university education, ensuring merit, not money, determines access.”

An analytical writer examines relationships objectively. Persuasive uses those relationships to argue for specific solutions.

Persuasive vs Critical:

Critical: “Whilst advocates claim reducing tuition fees would improve access, this overlooks implementation costs and potential quality reductions. Alternative funding models merit consideration, but each carries trade-offs requiring careful evaluation before policy change.”

Persuasive: “Critics worry about funding, but Scotland proves free university education works. Their model demonstrates that eliminating fees doesn’t compromise quality. It enhances it by attracting diverse talent. England should adopt Scotland’s approach immediately.”

Critically evaluates arguments from multiple perspectives. Persuasive advocates for one specific position whilst addressing counterarguments strategically.

How to Do Persuasive Writing

Don’ts of Persuasive Writing

Don’t rely solely on emotion without evidence. Persuasive writing requires logical arguments supported by credible evidence. Emotional appeals alone appear manipulative. Combine pathos (emotion) with logos (logic) and ethos (credibility) for effective persuasion.

Don’t ignore counterarguments entirely. Pretending opposing views don’t exist weakens credibility. Acknowledge alternative perspectives, then explain why your position remains superior. This demonstrates you’ve considered objections thoughtfully rather than dismissing them ignorantly.

Don’t use aggressive or condescending language. Hostile tone alienates readers rather than persuading them. Replace “Anyone who disagrees is obviously wrong” with “Whilst some hold different views, evidence suggests…” Respectful persuasion proves more effective than antagonistic assertion.

Don’t make unsupported claims or exaggerations. Overstatement damages credibility. Avoid absolute terms like “everyone knows,” “always,” or “never” unless genuinely accurate. Replace “This policy will definitely solve everything” with “Evidence suggests this policy significantly addresses the problem.”

Don’t confuse persuasion with propaganda. Academic persuasive writing maintains intellectual honesty. Present evidence fairly, acknowledge limitations, and avoid deliberately misleading readers. Ethical persuasion respects the reader’s intelligence whilst making your case compellingly.

Do’s of Persuasive Writing

Do establish credibility early. Demonstrate expertise through citing authoritative sources, acknowledging complexity, and showing a comprehensive understanding. Readers accept arguments from credible writers more readily than from those appearing uninformed or biased.

Do use concrete examples and evidence. Abstract arguments convince less effectively than specific, relatable examples. Replace “Many people struggle” with “Recent surveys show 68% of students report…” Concrete evidence makes abstract positions tangible.

Do structure arguments strategically. Present your strongest points first and last (primacy and recency effects). Address counterarguments after establishing your position, showing you’ve anticipated objections. Guide readers logically toward your conclusion.

Do appeal to shared values and common ground. Identify what you and readers likely agree on, then build arguments from that foundation. Starting with common ground reduces defensiveness, making readers more receptive to positions.

Do use clear, confident language with strong verbs. Replace passive constructions and hedging with direct statements. Instead of “It might be suggested that perhaps we should consider,” write “We must implement…” Confident language conveys conviction.

Do end with clear calls to action. Tell readers exactly what you want them to think, believe, or do. Vague conclusions waste persuasive momentum. Specify: “Therefore, students should contact their MPs demanding tuition fee reform.”

When All Three Writing Levels Work Together

The most sophisticated academic contexts strategically combine all four types.

Policy papers, grant proposals, and advocacy research integrate descriptive background, analytical examination, critical evaluation, and persuasive argumentation.

For example:

Descriptive foundation:

“Current NHS waiting times average 18 weeks for non-urgent procedures, affecting 6.5 million patients.”

Analytical examination:

“Analysis reveals waiting times correlate strongly with funding cuts and staff shortages, suggesting systemic resource issues rather than efficiency problems.”

Critical evaluation:

“Whilst some argue private sector partnerships could reduce waits, evidence from previous initiatives shows minimal sustained improvement whilst increasing costs and creating two-tier access.”

Persuasive conclusion:

“Therefore, the government must increase NHS funding by £8 billion annually to restore services, reduce waiting times, and prevent system collapse. The evidence overwhelmingly supports direct investment over privatisation alternatives.”

This integration demonstrates mastery:

- Establishing facts

- Analysing causes

- Evaluating proposed solutions critically

- Then, persuasively advocating for evidence-based action.

Progressive Levels Across Your Degree

| Academic Level | Focus | Required Writing Mode |

| Undergraduate (Year 1) | Foundation | Mostly Descriptive: Focus on showing you understand the basics. |

| Undergraduate (Final Year) | Specialisation | Mostly Analytical: Focus on comparing theories and finding gaps. |

| Masters / PhD | Originality | Dominantly Critical: Focus on evaluating evidence and creating new knowledge. |

The Hierarchy of Academic Writing

These three levels represent the complexity of your thought process. After auditing a lot of university rubrics, we’ve found that the higher the level, the higher the mark.

- Descriptive Writing (Level 1: The “What”)

- Analytical Writing (Level 2: The “How” and “Why”)

- Critical Writing (Level 3: The “So What?”)

Descriptive Writing

This is the baseline level. You are telling the reader what happened, who said what, or how a process works.

- Purpose: To provide background, define a setting, or state a theory.

- The Mark: Necessary, but if your paper is 80% descriptive, your grade is usually capped at a Pass or a 2:2.

- Example: “The NHS was founded in 1948 to provide healthcare that is free at the point of delivery.”

Grade Boundaries Defined By the UK Institutions

- First-Class Honours (1st, 1 or I): 70% or higher

- Second-Class Honours:

- Upper division (2:1, 2i or II-1): 60 – 69%

- Lower division (2:2, 2ii or II-2): 50 – 59%

- Third-Class Honours (3rd, 3 or III): 40 – 49%

Analytical Writing

This mode treats information as being broken down into its parts. You aren’t just stating facts; you are looking for relationships, patterns, and categories.

- Purpose: To examine the “mechanics” of a topic.

- The Bridge: You move from what a system is to how it functions under specific pressures.

- Example: “By examining the 1948 funding model alongside current demographic shifts, it becomes clear that the original structure did not account for an aging population.”

Critical Writing

This is the highest level of academic rigour. It requires you to judge the quality of evidence, identify biases, and propose alternatives. It is the core requirement for dissertation writing.

- Purpose: To evaluate and argue.

- The Reality: This is where you earn your First-Class or HD (High Distinction) marks.

- Example: “While the funding model was revolutionary for its time, current evidence suggests it is no longer sustainable; however, the proposed privatisation alternatives fail to account for socio-economic health disparities.”

Conclusion

Mastering descriptive, analytical, critical, and persuasive writing transforms academic performance from basic competence to genuine scholarly engagement.

Understanding when to describe, analyse, critique, and persuade separates adequate work from excellent work.

Different assignments demand different approaches, for example:

- Literature reviews require strong descriptive and analytical skills.

- Research papers need critical evaluation.

- Policy recommendations demand persuasive argumentation alongside analysis.

Developing flexibility across all four types makes you adaptable to any academic challenge.

Our expert assignment writing experts at FQ Assignment Help supports students in developing these crucial academic writing skills. Our qualified writers understand what critical engagement looks like across disciplines. Psychology expectations differ from business requirements.

Whether you need:

- Essay writing demonstrating critical analysis

- Dissertation development requires sophisticated evaluation

- Coursework integrating all three levels

- Research papers demanding rigorous assessment

We provide examples showing how critical thinking translates into written arguments.

We don’t just write for you. We show you how critical academic writing actually works.

Your ideas deserve expression at the highest academic level. We help you get there.